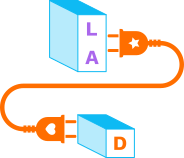

Linux Audio Development (LAD)

Plogue

Linux Audio developer interview with David Viens from Plogue

This interview was conducted by Amadeus Paulussen in 2025.

For readers unfamiliar with old sound chips, how would you describe your plugins, and what makes them special?

Thank you for this opportunity! This is going to be nerdy: We take old video game consoles and synthesizers apart, desolder the usually undocumented chips that they contain (the stuff that make up their signature sound), then place them on protoboard (editor's note: a tool used in electronics to create temporary circuits), and run a million tests on them.

We then try to replicate the test outputs with our own code. As we inevitably stumble unto implementation questions and wonder how a specific bit of silicon reacts to a specific edge case or stimuli, we then proceed to make even MORE hardware tests! This sort of loop can have many MANY iterations.

It's only after we are satisfied that nothing we can think of is OFF between our model and the real thing do we call it a day.

We almost always go over budget, in ways that would make any sane company declare a loss and move on. (See: Sunk Cost Fallacy).

We are quite an obsessive bunch, and that mentality is generally not so prevalent in typical get rich quick schemes.

We do this out of love and are lucky enough to make it a living. We are genuinely trying to preserve those sounds from extinction, in our own way.

How did you first get into reverse-engineering classic chips and turning that research into plugins?

In 2007 or so, I needed to find a product idea that would allow us to re-use the rompler/synth engine we had already designed for a 3rd party customer (Aria) for Garritan Instruments/MakeMusic.

Something that would be closer to our experimental and lo-fi roots. (We came to VST development from both an IDM and experimental techno DJ background, and a comp-sci background).

Meanwhile, in my spare time, I was reliving my youth collecting old game consoles and fixing them for fun, so I simply connected the two together.

Even though there were already quite a few VST plugins that tackled those kinds of sounds, I thought that there was nothing in there went deep enough, accuracy-wise, for my taste.

I knew we could do better, and Chipsounds (2009) was born out of that challenge.

Could you tell us a little about your own Linux journey? When did Linux first come onto your radar, and what motivated you to explore it?

When Seb and I were attending Université de Montréal in the mid 90s, all computer stations were SGI IRIX to begin with, so we already got our hands UNIX-dirty, as it were.

Then, a little bit later, when we shared a flat, we built a Linux router out of old PC parts so that both of us could share the (then new) broadband internet in Montreal.

Such routers are commodity now, but in those days, it was assumed that only one PC was ever connected to the modem.

We felt quite empowered when we got it working, as it was a much harder thing to pull off in the day.

When we started the company (2000), we obviously needed a Code Versioning System, so we also had a Linux machine that was closely managed by us just for this task.

But users have been asking us for literally decades for ports of our own products on Linux, and it never felt like an urgent necessity until a year or so ago.

I personally reached a saturation point and grew tired of bloat, enshitification, and the general sloppiness of programs, and the realization that the main OS vendors essentially controlled our machines, installed stuff we never asked for, spied on us, rebooted at random times, etc.

Microsoft's stance on TPM 2.0 and its requirements for W11 was the final straw for me.

I strongly felt that we had to offer an alternative for our existing customers to get rid of that dependency, and this particular company that gives very little regard to the ewaste they create.

(I always had similar grievances against Apple's rapid deprecation, too, so this is not limited to MS).

How did you approach your early steps—choosing a distribution, desktop environment, and so on?

We've had many discussions with peers who had already jumped in and that essentially got us enough data to make a mental pie chart of the music making Linux distro landscape.

It was quite obvious to us that the best ROI would be to target Debian derived distributions primarily, and get others to work as a bonus.

GNOME was also the first choice because Ubuntu.

Do you feel like you’ve “arrived” in a particular Linux setup, or are you still exploring the larger ecosystem?

Still learning and exploring because it's actually fun.

I have a pile of recycled Chromebooks and a box full of various SBCs (editor's note: Single-Board Computer), each running a different flavor, be it x64/AArch64, KDE/GTK, X11/Wayland, Debian-derived, Redhat derived, and the occasional Arch derived, and TRY and run our install scripts on those.

As I do very few things like everybody else, I had my own idea on how to release software as friction free as possible, all the while shipping only ONE zip file per product/CPU architecture, regardless of distros.

We REALLY REALLY didn't want another packaging multiplier here.

We already have too many SKUs (editor's note: Stock Keeping Unit) and targets as it is. And the list will grow.

What do you think motivates people to choose Linux as their operating system?

Control, I guess. To be honest, I never felt TOTALLY in control on Linux until I started seriously delving into it, and by that, I mean compiling my own kernel and rolling out a distro for personal experiments.

When you go that deep, it becomes intimate, much less scary and alien.

How did you approach porting your plugins to Linux? And were there any unexpected difficulties?

We always knew that the biggest hurdle would be UI-related.

We virtually use no 3rd party tools and frameworks, and especially not JUCE. (Getting into the whys would take more words than this entire interview and would hurt some feelings).

But it's relatively easy to port existing plugins to Linux if you've already been using that SDK, that's for sure, but we have no regret whatsoever. More effort on our end, but the same is true for the eventual personal rewards.

And again... control. So anyway, we initially thought, OK, we have a choice of X11 (a 40 year old framework with lots of legacy issues and jurisprudence), or a new shiny!

We rapidly learned that the audio world on Linux at large was not yet ready for the new shiny, but we are slowly starting a port to that now.

Were you ever concerned about the infamous Linux "fragmentation", and how has that turned out in practice?

That was the number one reason we didn't want to bother initially. But when you sit down and look at usage stats and what major DAWs like Bitwig are doing (basically telling you to use Ubuntu for best results), we thought, lets at least cover their users and see how it goes.

When installing the plugins as an Arch Linux user, I noticed you distribute them in .deb format. What motivated that packaging choice?

Release simplicity (for us), as mentioned earlier. Our main focus is what the pie chart tells us, and that's apt/dpkg distros first.

However! Since .deb is really just a big tarball+metadata file, I had the idea that it still could be used as a packaging format for other platforms as well since our products needed an installer script anyway on Debian due to each product shipping with 2 or more distinct .deb files—mirroring the architecture we use on Mac and Windows —

Our core framework: Plogue Aria - for legacy products -, and Plogue Fermata for stuff we worked on 2018 onward.

Think of those as our "JUCE" framework, it includes all the dynamically generating UI classes, DAW interfacing, product registration, etc.

Our new products are all based on that, but also ship with product-specific sub compiled libraries (usually for deep DSP/Emulation), UI assets, and preset files.

How big is the Plogue team today, and how do you divide responsibilities? Do you personally handle everything, from chip research to programming to UI/UX, or is it a collaborative process?

We have been a steady three people group full time since before Covid.

We used to be 6 at one point, but that is when we took the bulk of the development for one of our main partners.

At some point, that "division" was shut down, and we only kept the core team that focused on our own Plogue-branded products.

Right now, Seb does all the UI classes and is the main macOS developer, Hubert (madbrains) Lamontagne works 100% on emulation research.

While I do a bit of everything, from emulation code to support, showing my face in company videos, and generally pushing product ideas forward.

I really enjoyed using OPS7 and PortaFM—they felt very polished and smooth. What’s your general philosophy when designing user experience? And how important do you think UI/UX is in today’s crowded music-production market?

We do not put nearly enough thought into our UX as we should, to be honest.

Our focus and interests lie in emulation R&D so much that UX sadly becomes third rate citizen more often than not.

But, we feel our core user base can trade the occasional rough UX edges for sonic accuracy (at least, I hope they do).

I'm certainly not a fan of a lot of flashy-UI-but-bread-and-butter-DSP plugins that are legion, and will just be even more common with AI slop spreading like wildfire.

In the Cuckoo video, we saw your impressive workshop. How do you balance your time between coding and working with hardware?

Funny how perception goes. I just watched that and cringed that you had to see how lowkey my basement home lab actually is, with dangling wires, pipes, and all.

When we had an office (before we all went to work from home early Covid—and never went back), I actually had two separate labs, and either was much less crowded than this one, but I like this situation better personally.

You know, for those times when I wake up early in the morning and want to open up a specific piece of gear to double check something, only to realize *oh ***, it's at the office!

But your question touches on a very important point. It's really hard to separate work, leisure, and family time, even more so than coding vs working with hardware. The latter, I just usually do over the weekends—or as a reward of sorts—when done on company hours, if there is really such a distinction for me.

How much direct contact have you had with the Linux audio stack (ALSA, PipeWire, JACK, etc.)? Do you rely on any framework to abstract these layers?

In this rare instance, yes. We've been using and contributing to portaudio since its first initial releases.

That code was small enough, and flexible enough, for us to get behind. It also made sense to use this in case we would need to port our stuff to other platforms in the future, including Linux. We always like to keep doors opened—even if it took more than 20 years to take it.

So, we rarely touch the audio stack. I'm also using SDL2 for various experiments and tools on SBCs, and so the audio stack is always abstracted.

Have X11 or Wayland presented any challenges for you while developing your Linux builds?

Yes, touched a bit on this earlier. I guess Wayland is still in very early stages, so can't really comment yet.

But for X11, the biggest issues were centered around the user interactions with the windowing system that normal MacOS/Windows devs take for granted:

Clipboard, drag and drop... and ... you know, FILE AND MESSAGE DIALOGS, which need a 3rd-PARTY-COMMAND-LINE-APP-THAT-IS-DIFFERENT-ON-EACH-WINDOW-TOOLKIT-AND-MAY-OR-MAY-NOT-BE-INSTALLED-BY-DEFAULT (that one still blows my mind to this day).

What are your thoughts on modern plugin formats—especially CLAP—and on Steinberg making the VST3 SDK Open Source?

We were on board with CLAP relatively early on, as it was a step in the right direction for the industry.

VST2 was actually OK for a long time, it was broken for sure, but we all knew which parts to use collectively (the mine field was fully mapped, so to speak). VST3, however, was a big, convoluted disappointment.

Made plenty of things worse and not enough valid new ideas to justify killing its predecessor.

Especially the "MIDI is dead, it never existed actually, please move along" part.

Glad bare metal MIDI is (optionally) available and unadulterated in CLAP. It's critical for MPE (editor's note: MIDI Polyphonic Expression) transparency and so many legacy synth emulations.

The consensus is that opening up VST3 WAS a desperate move to counter the adoption of CLAP.

But, as Darth Vader said: "It is too late for me, my son".

You support both x86 and ARM. Do you see ARM becoming increasingly important for music-production workloads?

Yes, and I'm even already starting experimenting on riscv64. I think we need to be ready for everything.

Besides, as I repeat like a mantra, the more compilers and target platforms you run your code on, the more bugs you will find.

There are some bugs that can lurk in dark places and never cause issues by pure chance, due to different memory allocation logic and padding from a specific C/C++ compiler on a specific target for example.

But is ARM anything special for music? It's just affordable and heat efficient, so I guess yes?

How do you view the current state and future potential of GPU-accelerated audio processing?

I personally do not see the point for us and what we do. Our emulation algorithms are usually too single threaded to be parallelized.

Also, as an environmentalist and tech market skeptic, I don't want to contribute in any way to the rapid deprecation and price speculation of GPUs.

Your unlocking mechanism is quite unique. Is that a system you designed yourself?

I could say yes, but that would be a lie. The idea came from an old mid-2000s security company's blog post, and the concept was met with skepticism and quickly abandoned.

They never went through with it, afaik, nor patented it.

Gary Garritan suggested a similar concept as a licensing scheme for their virtual instruments. I liked the idea enough to use it globally for our shared frameworks.

You might not be aware, but u-he recently borrowed the idea (with our blessings—not that it was needed) and other companies potentially implementing it as I type this. See: u-he License Cards

We could someday have a virtual wallet of license cards that you could graphically flip.

It's like a membership card that you keep close... as your personal information that is visible on it. (And inside of it, using steganography).

Many developers feel constrained by the lack of iLok on Linux. What’s your perspective on copy-protection systems in general?

As you mentioned, our licensing scheme is unique. I feel users should be free and not be limited by the number of machines that they own and want to put their licenses on.

That’s the sort of flexibility I like too, having LOTS of test machines of various architectures, OSes, and specifications.

You have various PCs and laptops at home and in your studio? Use the same key, but hey, it has your name and address on it, "would be a shame if you were to lose it".

What are your thoughts on subscription models, rent-to-own, or hybrid models, like Bitwig’s update plan?

Again, I think more like a user than a sales person. I also align with the ideas of permacomputing.

I want to own permanent licenses, keep them as backup, and use those now or in 20 years if I feel like it.

There are people that use the same Plogue Bidule license they bought more than 20 years ago.

Do we lift an eyebrow when we get support requests from someone whose license is old enough to drink in all places in the world where liquor is legal?

Sure, but I have to do what I preach, right?

Have you ever considered open-sourcing any part of your work?

Touchy question, if there is any, especially with the rise of AI scrapers. Not having your code out there protects it from easy copycats that put no effort and try to outsell your work with themselves. I contribute to a few Open Source projects here and there, and that is only natural to give back when you use something (PortAudio), libsndfile), and generally MAME for my personal video game archeology research.

What has your experience been with the Linux users so far? Do they need more support than macOS or Windows users, or is that mostly a myth?

They need much less trivial support. It's something we greatly appreciate. So far, our typical Linux support ticket was written by someone that is computer literate and understands concepts of file systems, permissions, windowing, packaging, and often quite fluent with shell commands. We speak more or less the same language, if you will.

Many embedded musical instruments run on Linux. Do you see Linux’s efficiency on older or lower-powered hardware as an opportunity for wider adoption?

Some of our code recently shipped on a rather big commercial embedded Linux synth, and spent a good amount of time optimizing that code for its target chipset.

Brings me back to the joys of optimizing for 8bit hardware, where every cycle counts.

Note: I usually test my code on low to mid range hardware for that reason, too, it prevents us to get complacent.

That was, in retrospect, another important milestone that eased our own products towards Linux.

I am also secretly working on another Linux embedded something for fun.

Might spill the beans next year, or keep it as a fun hobby; who knows, keeping something as a hobby is something I should try someday.

What does your current day-to-day computer setup look like? You still work mainly on Windows, right? Can you imagine becoming a primary Linux user in the future?

This is precisely my current predicament. Been a die hard Windows user since Windows 3.1, and just had it with it.

My main workhorse is a few years old, 12 core Ryzen 9 with 64GiB RAM and RTX4070, running W11.

I am currently dual booting with Mint and trying to see how much of my work I can get done on it.

Microsoft Visual Studio, being my main IDE for nearly 30 years, will be hard of reflexes and muscle memory.

Might try to use that in WinBoat to start, then progressively switch to Studio Code, but good IDEs are rare.

Don't get me started on XCode.

I recently described using Linux as being like "building an instrument, rather than just learning to play one." Does that metaphor resonate with you?

True, but the real danger here is becoming a goat farmer in the process (IYKYK).

AI is on everyone’s mind these days. What are your thoughts on its impact on art, music, and human creativity?

As of time of answering, it's a total shitshow. Move fast and break things is doing its madness as usual.

I try to experiment and learn about what it can do to keep up to date and know what I'm talking about, but the impact of it is relatively minor for Plogue for the time being.

But I already do see a few of my peers that are struggling to remain relevant with their "bread and butter—DSP-with-a-nice-facade" when some stranger can vibe code equivalents in a weekend.

I have been personally using some LLMs as a teacher for some unrelated experiments recently; I just ask it how specific sub tasks should be approached. Then I take the notes it spews and print them, try it myself with the computer turned off. That's the only way I found not to let it do it all for you, as we all have our lazy days.

Especially important not to develop long term brain rot. Studies are only brushing the surface here. Retrospect will be ugly, I fear.

As far as how I feel about its impact on the overall art and music creativity landscape?

My opinion shifts daily on this, I wouldn't want to commit a permanent answer to print like this at this point in time.

I can only say that it's not going anywhere, and we must collectively learn to control it and not let mega corps/drug pushers rot our brains.

Thank you again for your time, and for bringing your wonderful plugins to Linux. 🤓 Is there anything you’d like to add that we haven’t touched on?

You have covered way more than I thought!

It was a pleasure and an honor.